Bishop Spong interviewed in his home on August 17, 2013

Jack speaks about his new book The Fourth Gospel: Tales of a Jewish Mystic Listen to the extended interview here

Bishop Spong interviewed in his home on August 17, 2013

Jack speaks about his new book The Fourth Gospel: Tales of a Jewish Mystic Listen to the extended interview here

I’m on vacation so I don’t get to preach this coming Sunday. But if I did, I suspect that I would move the Commemoration of St. Mary to Sunday and take the opportunity to explore the life and witness of this amazing woman. Today the Church celebrates the feast of St. Mary the Mother of Jesus or as it is still called in the Roman Catholic Church The Feast of the Assumption of St. Mary into Heaven. This enigmatic woman has remained in the shadows for centuries. All too often the epithet “virgin” has been applied to the young woman who fell pregnant so long ago. So on this festival day I this re-post this sermon which I preached a couple of years ago in which I asked some questions about Mary. At the time I was reading Jane Schalberg’s “The Illegitimacy of Jesus”, John Shelby Spong’s “Born of a Woman” and “Jesus for the Non Religious” along with John Dominic Crossan and Marcus Borg’s “The First Christmas” and this sermon is laced with their scholarship. As always the written text is but a reflection of the sermon preached on the Fourth Sunday of Advent 2009.

Sadly, one doesn’t have to travel too far into the past to arrive at the time when women’s voices were not heard. Indeed, in the Lutheran church, it was only a few short decades ago. For most of us that time is within our own lifetime. For generations, men have told our sacred stories. Men have decided which stories made it into the canon of Sacred Scriptures. Men have interpreted the stories that were allowed to be told. Men have translated, taught, and commented upon those stories from pulpits, in universities, in seminaries, in commentaries and in the public square. Continue reading

This past weekend, The Emerging Church of Springfield, MO. hosted a conference on the Future of Progressive Christianity at which Bishop John Shelby Spong spoke, as only Jack can, on the history of Christianity’s “wrongful diagnosis of what it means to be human” and pointed to a new vision for Christianity’s future. Many thanks to Dr. Roger Ray and the good people of the Community Christian Church for organizing and sharing this conference!!!

This past weekend, The Emerging Church of Springfield, MO. hosted a conference on the Future of Progressive Christianity at which Bishop John Shelby Spong spoke, as only Jack can, on the history of Christianity’s “wrongful diagnosis of what it means to be human” and pointed to a new vision for Christianity’s future. Many thanks to Dr. Roger Ray and the good people of the Community Christian Church for organizing and sharing this conference!!!

I am indebted to Bishop John Shelby Spong for his insights into the Book of the Prophet Hosea. Without Jack’s thoughtful portrayal of Gomer, I would not have recognized her as the Leanne Battersby of her time. Also, thanks to Marcus Borg for his definition of the verb “believe”!

I am indebted to Bishop John Shelby Spong for his insights into the Book of the Prophet Hosea. Without Jack’s thoughtful portrayal of Gomer, I would not have recognized her as the Leanne Battersby of her time. Also, thanks to Marcus Borg for his definition of the verb “believe”!

Listen to the sermon:

For those unfamiliar with Corrie, here’s a sample of the first 50 years:

June 9, 2013 – Readings: 1 Kings 17:17-24 and Luke 7:11-17

Listen to the sermon here

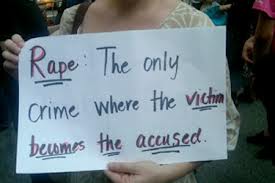

May 31st is the day the Church commemorates “The Visitation” the story of Mary’s visit to Elizabeth as it is recorded in the Gospel According to Luke 1:39-56. Since reading Jane Schalberg’s “The Illegitimacy of Jesus”, I can’t help but wonder if Mary’s visited her cousin Elizabeth or escaped to her cousin Elizabeth seeking protection for the crime of being raped in a culture that all too often blamed the victim. Historians estimate that Mary may have been all of twelve years old when she became pregnant. There is ample evidence in the New Testament accounts of Mary’s story that suggest that she may indeed have been raped. So rather than sweep the possibility under the rug, on this the Feast of the Visitation, I’m reposting a sermon I preached a few years ago during Advent. I do so because women young and old continue to be raped and to this day, are forced to flee from the accusations and persecutions of cultures that continue to blame the victim. What follows is a written approximation of the sermon which in addition to Jane Schalberg is also indebted to John Shelby Spong’s “Born of a Woman” and “Jesus for the Non Religious” along with John Dominic Crossan and Marcus Borg’s “The First Christmas”.

May 31st is the day the Church commemorates “The Visitation” the story of Mary’s visit to Elizabeth as it is recorded in the Gospel According to Luke 1:39-56. Since reading Jane Schalberg’s “The Illegitimacy of Jesus”, I can’t help but wonder if Mary’s visited her cousin Elizabeth or escaped to her cousin Elizabeth seeking protection for the crime of being raped in a culture that all too often blamed the victim. Historians estimate that Mary may have been all of twelve years old when she became pregnant. There is ample evidence in the New Testament accounts of Mary’s story that suggest that she may indeed have been raped. So rather than sweep the possibility under the rug, on this the Feast of the Visitation, I’m reposting a sermon I preached a few years ago during Advent. I do so because women young and old continue to be raped and to this day, are forced to flee from the accusations and persecutions of cultures that continue to blame the victim. What follows is a written approximation of the sermon which in addition to Jane Schalberg is also indebted to John Shelby Spong’s “Born of a Woman” and “Jesus for the Non Religious” along with John Dominic Crossan and Marcus Borg’s “The First Christmas”.

Sadly, one doesn’t have to travel too far into the past to arrive at the time when women’s voices were not heard. Indeed, in the Lutheran church, it was only a few short decades ago. For most of us that time is within our own lifetime. For generations, men have told our sacred stories. Men have decided which stories made it into the canon of Sacred Scriptures. Men have interpreted the stories that were allowed to be told. Men have translated, taught, and commented upon those stories from pulpits, in universities, in seminaries, in commentaries and in the public square. Continue reading

Today’s Trinity Sunday sermon owes much to John Shelby Spong’s book a “New Christianity for a New World”

Today’s Trinity Sunday sermon owes much to John Shelby Spong’s book a “New Christianity for a New World”

You can listen to the sermon here then watch the tail end of the Wolf Blitzer interview mentioned in the sermon.

We sang Shadow and Substance as our Hymn of the Day: view it here

The splendid preacher Clay Nelson of St. Matthews-in-the-City, Auckland, New Zealand, opened me up to a new way of seeing Pentecost. Nelson tells this lovely little story written by fellow Kiwi Judy Parker, entitled simply “The Hat.”

A priest looked up from the psalms on the lectern, cast his eyes over all the hats bowed before him. Feathered, frilled, felt hats in rows like faces. But there was one at the end of the row that was different. What was she thinking, a head without hat. Was like a cat without fur. Or a bird without wings.

That won’t fly here, not in the church. The voices danced in song with the colours of the windows. Red light played along the aisle, blue light over the white corsage of Missus Dewsbury, green on the pages of the Bible. Reflecting up on the face of the priest. The priest spoke to the young lady afterwards: “You must wear a hat and gloves in the House of God. It is not seemly otherwise.”

The lady flushed, raised her chin, and strode out. “That’s the last we’ll see of her,” said the organist.

Later: The organ rang out; the priest raised his eyes to the rose window. He didn’t see the woman in hat and gloves advancing down the aisle as though she were a bride.The hat, enormous, such as one might wear to the races. Gloves, black lace, such as one might wear to meet a duchess. Shoes, high-heeled, such as one might wear on a catwalk in Paris. And nothing else.

Now some people might ask, “Is this a true story?” And I’d have to answer that this story is absolutely true! Now for some that answer might not be enough and they’d want to know, “Did this actually happen?” Well, I’d like to think so. But I doubt that it actually happened. But whether it actually happened or not, most of us know that the truth in this story lies in the power of metaphor.

Metaphor, which literally means: beyond words. The power of metaphor is in its ability to point beyond itself to truths beyond those that are apparent. And the metaphor in this story points us to buck-naked truths about tradition, worldly power, patriarchy, hierarchy, orthodoxy and many more truths about the very nature of the church itself and religion in general. It doesn’t matter whether or not this actually happened or not. What matters is what we can learn about ourselves and our life together from this story. Continue reading

Reposted today as the Church commemorates the life and witness of Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

When I was just a teenager, I was introduced to the writings of Dietrich Bonhoeffer by a wise Lutheran Pastor. I remember devouring Bonhoeffer’s “Life Together” and “Letters and Papers from Prison”. To this day, I credit Bonhoeffer for making me a Lutheran. While a great deal of water has flowed under a good many bridges since I was first enamoured of Lutheran theology, to this day I am grateful to that wise old Lutheran pastor who gave me my first taste of Bonhoeffer. Of late, there has been much ado about a little phrase that has been extracted from Bonhoeffer’s work: “religionless Christianity”.

(click here for full quotations from Letter and Papers from Prison)

“It is not for us to prophecy the day when men will once more ask God that the world be changed and renewed. But when that day arrives there will be a new language, perhaps quite non-religious. But liberating and redeeming as was Jesus language. It’ll shock people. It’ll shock them by its power. It’ll be the language of a new truth proclaiming God’s peace with men.” Bonhoeffer: Agent of Grace

Tragically, Bonhoeffer was executed before he had the opportunity to expand on his idea of Christianity beyond religion. The phrase “religionless Christianity” has intrigued agnostics, atheists, humanists, liberal christians and progressive christians. Eric Metaxas, author of “Bonhoeffer” dismisses the idea that Bonhoeffer was anything but a serious, orthodox Lutheran pastor right up to the end.

Despite the historical evidence of Bonhoeffer’s religious orthodoxy, the notion of religionless Christianity will not die. Bishop John Shelby Spong is among those who have tried to build on Bonhoeffer’s phrase and his book “Jesus for the Non Religious” has certainly moved the conversation along among progressive christians.

The dream of religionless christianity has moved well beyond Bonhoeffer as twenty-first century christians wrestle with archaic images of God and move beyond the religious trappings of traditional christianity. The notion of moving beyond religion has always intrigued me. Years ago, while studying Hinduism my professor offered a definition of God from one of the Vedas: “God is beyond the beyond, and beyond that also”. As I continue to explore the life and teachings of the man none as Jesus of Nazareth it becomes more and more evident that such a definition is compatible with his portrait of God. Jesus of Nazareth attempted to move his co-religionists beyond their religious images of God. What might our images of God become if we move beyond the idols offered to us by the religion of Christianity? Might we move toward images of God that more closely resemble the teachings of Jesus by moving toward a religionless christianity?

Sometimes we can better reflect upon our own tradition from the perspective of another tradition. In the video below, twentieth century philosopher and theologian Alan Watts explores the concept of the Religion of No Religion.

“Beyond the Beyond and Beyond that also.” Letting go of our images is the gift of faith that moves us beyond religion. I can hear Jesus call us to let go!

A Good Friday Sermon preached at Holy Cross Lutheran Church in 2012

The memory of it still haunts me to this day. I was 18 years old. Some friends of mine from church convinced me to go to a big youth gathering. I don’t remember who sponsored the gathering, I do remember that most of the Lutheran youth groups in the greater Vancouver area were in attendance and various Lutheran pastors were involved in the leadership. At some point near the beginning of the event we were each given a small nail, divided into groups and asked to line up behind one of the three wooden crosses that were laying in the hall. We were then given our instructions. We were about to hear a dramatic reading of the Gospel According to John’s account of the crucifixion. When the reading was over we would be invited to proceed to the cross nearest us, knell down, take a hammer, and drive our nail into the cross. With each blow upon the nail we were asked to remember our own responsibility for the death of Jesus. We were asked to remember that it was we who had crucified Jesus, for we were the guilty sinners for whom Jesus died. It was a powerful, gut wrenching experience that still haunts me to this day.

The memory of it still haunts me to this day. I was 18 years old. Some friends of mine from church convinced me to go to a big youth gathering. I don’t remember who sponsored the gathering, I do remember that most of the Lutheran youth groups in the greater Vancouver area were in attendance and various Lutheran pastors were involved in the leadership. At some point near the beginning of the event we were each given a small nail, divided into groups and asked to line up behind one of the three wooden crosses that were laying in the hall. We were then given our instructions. We were about to hear a dramatic reading of the Gospel According to John’s account of the crucifixion. When the reading was over we would be invited to proceed to the cross nearest us, knell down, take a hammer, and drive our nail into the cross. With each blow upon the nail we were asked to remember our own responsibility for the death of Jesus. We were asked to remember that it was we who had crucified Jesus, for we were the guilty sinners for whom Jesus died. It was a powerful, gut wrenching experience that still haunts me to this day.

I wasn’t the only young person who wept buckets that day. I immersed myself into the ritual act as I recounted inwardly the list of my own sins. Together with my friends, we left that hall believing that Jesus died because of us. We left judged, convicted, guilty, tormented, anguished, and full of hope, for we knew that Jesus had died to save us from our sinfulness. Like so many who have gone before us and like so many who will gather on this Good Friday, we left that hall believing that God sent Jesus to die for us; to pay the price for our sin. Continue reading

The Church’s Good Friday obsession with talk of “sacrifice for sin” has been breed into the bones of this particular preacher. I have been trained to speak the language of the Church. I know full well the many doctrines of atonement that have been proposed to explain the reasons Jesus died upon a cross. I’ve been studying the historical context and the theological consequences of Jesus’ death for more years than I care to admit. Yet every year, I find myself wanting to book a vacation or call in sick so that I can avoid the awesome task of preaching on Good Friday.

I’ve put it off tackling the Good Friday texts as long as I dare. So today, I picked up my copy of “The Last Week” by John Dominic Cross and Marcus Borg, together with my copies of John Shelby Spong’s “Resurrection: Myth or Reality” and “Jesus for the Non Religious” and spent the day in pursuit of a sermon.

What follows is not the sermon I will preach on Good Friday, but rather, the notes I made to remind myself not to fall into the trap of talking about the events surrounding Jesus’ death in the way I was trained to speak of those events. I offer up my notes hoping that those who are engaged in the struggle of grappling with how to talk about the cross in the 21st century might find some solace in a fellow struggler’s ruminations.

For those of you who don’t have to come up with a sermon for Good Friday, I offer these notes as my humble attempt to see beyond the rhetoric about the cross to the Good News. As always I am indebted to Dom and Jack for their scholarship.

There are many ways in which our focus upon the cross is disturbing. Not the least of which is the way in which we as Christians tend to talk about the crucifixion as Jesus’ passion. I have always thought it a tragedy that we should describe the events of Jesus’ crucifixion as Jesus’ passion. I’ve always understood talk of an individual’s passion to be concern with those things that people lived for. And so to insist that Jesus’ lived to die a horrible death might sooth those who seek to turn Jesus into some sort of preordained blood sacrifice.

But for those of us who look to Jesus in search of the face of God, such talk seems is indeed a crime against divinity. For what kind of petty, sadistic god would engineer the birth of, foster the life of, and then engineer the death of a beloved child. Surely such a god is no more than a wicked illusion of our own making.

I wonder what Jesus himself would make of the god we have created. I wonder what Jesus himself would make of our Good Friday commemorations? I suspect that if Jesus is anything like the accounts of his life suggest, he would be mortified, and I mean that literally…I think that Jesus would be mortified …mortified ie shamed to death…of what has become of his life’s passion; for if Jesus’ was passionate about anything, he was passionate about life. Jesus declared, “I have come so that you may have life and live it abundantly.” Jesus’ passion was about living. Living fully, abundantly. Continue reading

Re-posted from last year: On Maundy Thursday, followers of Jesus will gather together to remember what we have been told about the night before Jesus died. In our community we will begin with a ritualized washing of hands, then dine over a simple meal of soup, wine and bread. Over the meal we will talk together about the events of Jesus’ life, paying special attention to what we have been told about the Last Supper and Jesus’ betrayal. As the meal and the conversation comes to a close, we will take bread, give thanks bless it and give it to one another saying, “The bread of Christ given for you.” Then we will take a glass of wine give thanks and pass it to one another saying, “Christ poured out for you.” Then we will strip our sanctuary in preparation for what the morrow brings.

On Maundy Thursday, followers of Jesus will gather together to remember what we have been told about the night before Jesus died. In our community we will begin with a ritualized washing of hands, then dine over a simple meal of soup, wine and bread. Over the meal we will talk together about the events of Jesus’ life, paying special attention to what we have been told about the Last Supper and Jesus’ betrayal. As the meal and the conversation comes to a close, we will take bread, give thanks bless it and give it to one another saying, “The bread of Christ given for you.” Then we will take a glass of wine give thanks and pass it to one another saying, “Christ poured out for you.” Then we will strip our sanctuary in preparation for what the morrow brings.

In this post I have included a copy of the worship bulletin for this liturgy of suppers. It can be downloaded here. to be printed double-sided

21st century minds often find it difficult to reconcile the gospel accounts of this evening with. So, in place of the homily, we will discuss our struggles to understand the events of this evening in light of all that we have learned together.

For those of you who have asked, a copy of a previous Maundy Thursday homily is included here. This homily was preached in 2007 and while I am tempted to make some changes to it in light my own struggles to come to terms with the gospel accounts, I offer it unaltered, trusting that others may see in it the early stirrings of my own desire to discover a more progressive Christianity. At the time I had just completed reading Marcus Borg and John Dominic Crossan’s “The Last Week” and John Shelby Spong’s “Jesus for the Non-Religious” and their work permeates the homily.

Maundy Thursday 2007:

It’s a strange night. For several decades after the Resurrection, Jesus’ followers were known as the People of the Way, or the Followers of the Way. Almost 2000 years separate the first followers of Jesus from 21st century Christians.

I wonder if the early People of the Way would have as much difficulty recognizing modern Christians as Jesus’ followers as we modern Christians have understanding the practices of the People of the Way.

The People of the Way understood Jesus to be the embodiment of what can be seen of God. Jesus shows us who God is and Jesus shared with his followers his vision of God’s justice. Continue reading

Yesterday’s post in which I mentioned panentheism certainly prompted some interesting questions from various readers. So, even though I’ve written, preached and posted about panentheism many times, I thought I’d provide a fuller explanation of what I mean when I use the this word which I believe provides a way of articulating our reality that is both helpful and hopeful.

Yesterday’s post in which I mentioned panentheism certainly prompted some interesting questions from various readers. So, even though I’ve written, preached and posted about panentheism many times, I thought I’d provide a fuller explanation of what I mean when I use the this word which I believe provides a way of articulating our reality that is both helpful and hopeful.

Let me begin by saying, that panentheism is, in and of itself, an evolving term. The term can be found in the works of German philosopher G.W.F. Hegel, process theologian Alfred North Whithead, and more recently in the work of Juergen Moltmann, Matthew Fox, Philip Clayton and Marcus Borg. The word itself is made up for three Greek words: pan = all, en = within, theism = god. Panentheism is used to describe God as ONE who is in everything. Panentheism (unlike pantheism) does not stop with the notion that God is in everything, but goes on to posit that everything is God. God is in the universe and God transcends the universe. God is greater than the sum total of the universe. But the universe cannot be separated from God. We are in God and God is in us. God breathes in, with, and through us.

The term panentheism is proving helpful to Christians in the 21st century who are working to articulate our faith in light of all that we are learning about the universe. It is also invaluable to those of us who have a deep reverence for creation and are seeking ways to live in harmony with creation by treading lightly upon the earth. Panentheism is also a concept present in many faiths and provides us with a common way of speaking together about our Creator. But like all language the term fails to fully capture the nature of the Divine. It is merely a tool to help us think beyond the idols we have created to function as objects of our worship.

The Apostle Paul insisted that God is “the One in whom we live and breath and move and have our being.” (Acts 17:28) As we look towards the heavens, we see an ever expanding new story of who we are. Just as Paul struggled to find ways to articulate the nature of the Divine to his contemporaries, Christians continue in every age to find ways to articulate the nature of the Divine to each new generation. We do not abandon the wisdom that has been offered by those who have gone before us. But we cannot ignore the wisdom that is being revealed to us here and now in our time and place within the communion of saints.

Below is a video that I have shown to Confirmation students (ages 12-15) as we begin to explore the great religious questions that have inspired wisdom seekers from the beginning of human consciousness: Who am I? What am I? Where do I come from? Why am I here? Where am I going? etc. The responses of young people inspire me! I cannot wait to see what they will reveal to us about the nature of our reality! As you watch this video, I offer you a benediction. It is a blessing that I have adapted with permission from the work of John Shelby Spong.

God is the source of life, so worship God by living,

God is the source of love, so worship God by loving.

God is the ground of being, so worship God by having the courage

to be more fully human; the embodiment of the Divine.

This is a fascinating conversation that explores the role of Progressive Christianity in the life of the church.

Bishop John Shelby Spong, Rev. Dr. Jay Emerson Johnson, Dr. David Hollinger and Rev. Byron Williams discuss the mainline church and liberal Christianity at the Pacific School of Religion.

Having worked our way through the Living the Questions 2 and Saving Jesus dvd series, our Adult Education Class is using the book: Living the Questions: The Wisdom of Progressive Christianity as a frame for our review of progressive Christian theology. Each week I will post the video clips that were used during the class. This week’s class consisted of an introduction as well as an exploration of what it means to move beyond definitions of the Divine toward the reality of unknowing.

Thinking Theologically

“We must get away from this theistic supernatural God that imperils our humanity and come back to a God who permeates life so deeply that our humanity becomes the very means through which we experience the Divine Presence.” John Shelby Spong

As Advent draws to a close, our readings turn toward the woman from Nazareth known as Mary. This enigmatic woman has remained in the shadows for centuries. All too often the epithet “virgin” has been applied to the young woman who fell pregnant so long ago. I have been asked to post a sermon which I preached a couple of years ago in which I asked some questions about Mary. At the time I was reading Jane Schalberg’s “The Illegitimacy of Jesus”, John Shelby Spong’s “Born of a Woman” and “Jesus for the Non Religious” along with John Dominic Crossan and Marcus Borg’s “The First Christmas” and this sermon is laced with their scholarship. As always the written text is but a reflection of the sermon preached on the Fourth Sunday of Advent 2009.

Sadly, one doesn’t have to travel too far into the past to arrive at the time when women’s voices were not heard. Indeed, in the Lutheran church, it was only a few short decades ago. For most of us that time is within our own lifetime. For generations, men have told our sacred stories. Men have decided which stories made it into the canon of Sacred Scriptures. Men have interpreted the stories that were allowed to be told. Men have translated, taught, and commented upon those stories from pulpits, in universities, in seminaries, in commentaries and in the public square.

Today, as more and more women take on the tasks of translating, interpreting, writing, teaching, preaching and imagining the texture of our sacred stories are changing in ways that our mothers and grandmothers may not have been able to imagine. This morning, I’d like to ask you to imagine with me a radical re-telling of the birth narratives; a re-telling based on the New Testament and the hidden gospels of the apocrypha; a retelling based on good sound historical scholarship; a retelling grounded in the ways of the world; a retelling by women; religious women, scholarly women, women trained in Hebrew, Greek, Latin, theology, doctrine, and the ways of the world.

Our story begins thousands of years ago in the occupied territories of Palestine were being a woman was a very dangerous and even death defying occupation. It is the story of a young girl; who couldn’t have been more than about 12 or 13, who fell pregnant. Notice the verb, it is chosen deliberately. The heroine of our sacred story is a young girl, a child, who fell pregnant. A dangerous and fall one for which the penalty was clear, for there was no ambiguity in the law, such fallen women were subject to stoning; stoning unto death.

But before I tell you this story, let me tell you another story. It’s the story of a woman who made it into the sacred halls of academia. She was a daughter of the Roman Catholic Church who against all odds managed to earn a PHD and teaches at a Roman Catholic University in Detroit. In 1987, when she dared to publish her scholarly account of our fallen heroine, she faced the wrath of the men in academia, who poo pooed her work and discounted her evidence without so much as a by your leave. This much she had expected, what she didn’t expect was the violence or the strange characters who showed up at her lectures hurling more than verbal insults; and she certainly didn’t expect to wake up in the middle of the night to find her car burning out in her driveway. The police told her to keep a low profile. She did for a while, but then people outside the academy picked up her book and the odd reporter quoted her theories and that’s when the death treats got really serious. You may not have heard of this obscure New Testament Scholar, but Jane Schaberg is a hero to many female biblical scholars, for daring to speculate on exactly how a young girl may have fallen pregnant 2000 years ago.

You see then like now, rape was not just a random crime committed by isolated individual men. Then like now, rape was a military tactic designed to terrorize an occupied population. Jane Schaberg uncovered, what many believe to be a deep dark family secret about a young woman, a child who fell pregnant a long time ago and fled for her life. She wasn’t the first to talk about it. There were men in the past that had dared to speculate about it and felt the wrath of the institution.

Some say the evidence is clear, if you’re willing to see it. After all there was a large cohort of Roman soldiers encamped near Nazareth. The people of Nazareth had participated in an uprising against their oppressors and the Roman’s had raided Nazareth in retaliation. There are numerous Jewish accounts of Roman raids that include details of strategic rapes. Could our young heroine be the victim of such a rape?

There are New Testament scholars who ask you to simply consider the New Testament story of Jesus’ audacious first sermon in Nazareth. What could have made the good people of Nazareth so angry that they wanted to kill Jesus? Nazarenes were accustomed to listening to itinerate preachers make all sorts of outlandish claims. But this Jesus was a mamzer Jewish texts written within 500 years of his birth attest to it. Historians do not even dare to translate mamzer for fear of reprisals. I won’t translate it for you now, not out of fear but rather because there are children present. I’ll let you guess the English term we used to use to describe a child born without benefit of wedlock a term that is now used to describe many a man. Could Jesus’ neighbours have been offended that this mamzer had dared to occupy their pulpit?

Deuteronomy 23 is clear, “A mamzerim shall not enter into the congregation of the Lord; even to his tenth generation shall he not enter into the congregation of the Lord.” The writer of the Gospel of Matthew alluded to Jesus status as a mamzer in his very first chapter. The writer traced Jesus lineage back through four women who could be described as fallen women. These four women by the standard of the day in which this story was told, these four women were sexually tainted women, “shady ladies” a couple seductress a couple of prostitutes and an adulterer. These women: Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, and Bathsheba, were all under the shadow of scandalous sexual activity and the inclusion of these women in Jesus genealogy should alert us that we should expect another women who becomes a social misfit by being wronged.

But if imagining Jesus as a mamzer is offensive to you, set it that aside for a moment and let’s look at the Gospel according to Luke and try to see past our rose coloured glasses. The Gospel of Luke tells the story from the perspective of Mary. Over the years generations of listeners and readers have taken the author’s depiction of Mary and created an image of Mary that is larger than life.

The popular image of Mary paints her as the ideal woman, the ideal woman that none of us could ever live up to. The image of Mary is that of both virgin and mother, meek and mild, obedient and perfect. She is impossible as a role model of course and totally unreal.

In order to see Jesus we have to move beyond the popular image and look at what the author of Luke actually wrote about Mary. It’s in the words of the Magnificat that the author reveals the revolutionary Mary. The Magnificat is the song Mary sings when she meets Elizabeth. When read in its original Greek it is clear that Mary bursts into song. The text of the song is a revolutionary text full of historical meaning that would have been clear to it’s first century listeners, but the radical nature of this song has been lost as successive generations have set it to music and prettied it up as best they can. But in the first century Mary was a revolutionary figure. The author of the gospel of Luke, does not intend her to be “mother Mary meek and mild.” The references, with which the author and his audience would be familiar, are to heroines of Israel, to revolution and to war.

The song of the Magnificat is written in the style of two other songs from the Scriptures that would have been so familiar to the gospel writer’s audiences. Elizabeth addresses Mary as “Blessed…among women.” This was not a normal greeting. There are only two other texts in the Scriptures where this phrase is used. In the Book of Judges, Deborah, who was herself a prophetess and a judge of Israel sings, “Blessed among women be Jael”. And Deborah’s song goes on to tell us who Jael was and what she did. “Most blessed of women be Jael, the wife of Heber the Kenite, of tent-dwelling women most blessed. He asked for water and she gave him milk she brought him curds in a lordly bowl. She put her hand to the tent peg and her right hand to the workman’s’ mallet; she struck Sisera a blow, she crushed his head, she shattered and pierced his temple. He sank, he fell, he lay still at her feet; at her feet he sank, he fell; where he sank, there he fell dead.” Sisera was the commander of the Canaanite army. Deborah the ruler of Israel promised her general Barak, that Sisera would be delivered into his hands. So, Barak summoned up his troops and went into battle. As the Israelites seemed to be winning Sisera fled to the camp of his ally Heber the Kenite—who was married to Jael. Jael invites Sesera into her tent, offers him hospitality, and after a meal of milk and curds he falls asleep. While Sesera the enemy of the Israelites lies sleeping, Jael bashes a tent peg through his skull. And for this Jael is heralded as a great heroine of the people as Deborah sings her praises calling her blessed among women.

The second woman in the Scriptures who is hailed as blessed is Judith. Judith is also a heroine of Israel. Her story takes place as the Assyrians are laying siege to the town of Bethulia, where the Israelites have almost run out of water. Judith leaves the city, allows herself to be captured by they Assyrians and taken to their leader Holofernes. Judith pretends to be fleeing from the Hebrews and offers to betray them to Holofernes. Holofernes welcomes Judith and offers her hospitality.

Judith then seduces Holofernes. After taking him to bed, while he is sleeping, Judith chops off his head with his own sword. She tucks his severed head in her food bag, escapes and returns to the Israelites. When she returns Uzziah, one of the elders greets her with the words, “O daughter, your are blessed by the Most High God above all other women on earth.” Later at a party giving to celebrate her victory, Judith sings a song to God in which God’s support for the oppressed is proclaimed, just as Mary proclaims that the rich and mighty will be brought down.

The author of Luke makes other references in his narrative, which would have been equally clear to his first century audiences. Starting with that angel who appears to Mary. Read Judges 13 for a similar story of an angel appearing to a woman and declaring that she will conceive and bear a son. There you will find the story of Manoah ‘s wife and the miraculous conception that led to Samson’s birth.

Today the angel Gabriel is usually portrayed as a white effeminate male in a flowing white gown. But this depiction is not one that would have been recognized as Gabriel in the first century. Back then Gabriel was understood to be the angel of war and he was associated with metal and metal workers. The mere mention of Gabriel would have conjured up images of a fierce warrior clothed in amour, ready to do battle on the side of the Israelites.

The name that the warrior angel insists on for Mary’s child is Jesus. Jesus is the Greek form of the Hebrew, Joshua. Joshua succeeded Moses, conquered Canaan and established the twelve tribes of Israel in the Promised Land. Joshua was a hero and a warrior. The author of the gospel of Luke makes a deliberate link suggesting to his readers that Jesus will follow in the same mould.

First century audiences would have been very familiar with the parallels being drawn. Mary is being clearly established as a revolutionary heroine, in a nationalistic and violent tradition. And the Magnificat is a song of revolution which proclaims the downfall of the prevailing order. The Magnificat is a rallying cry to overturn the established order of wealth; a tune intended to rouse the troops.

The author of the Gospel of Luke knew exactly the kind of Messiah the people are waiting for. Two thousand years ago in the dusty streets of Jerusalem, revolutionary ideas passed from house to house. The bitterness of Roman bondage had robbed the Jewish people of their ideals but not their Messianic hope. Jewish eyes continued to peer through the darkness imploring hands were still lifted towards heaven and the plaintive cry of Israelites begged the question: “When will the dark night be over?” In their despair, the idea of revolution was born. It was linked to the coming Messiah; the promised Saviour whom they were counting on to free them from oppression; the longed for a Saviour to lead Israel to freedom. That was the kind of Messiah the Jews living in the first century wanted.

The author of the gospel of Luke knows his audience well and he plays to their expectation of a Messiah who will lead them in battle; a military hero. The author presents Mary as a woman, who has a vision of what God will do. Mary’s song is the song of a heroine of Israel, for blessed is she among women. Mary’s song echoes the words of the Hebrew Scriptures: “My soul magnifies the Most High, and my spirit rejoices in God my Saviour, who has looked with favour on the lowliness of God’s servant: Surely, from now on all generations will call me blessed; for the Mighty One has done great things for me, and holy is God’s name. God’s mercy is for those who revere God from generation to generation. God has shown strength with God’s arm, and has scattered the proud in the thoughts of their hearts. God has brought down the powerful from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; God has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich away empty. God has helped God’s servant Israel, in remembrance of God’s mercy, according to the promise God made to our ancestors, to Abraham and Sarah and to their descendants forever.”

Mary’s song takes on new meaning when heard within the context of violence and rape. Mary’s song takes on new meaning in our world where rape continues to be a military tactic. Let me give you the figures according to a report by the United Nations dated this past June. In Rwanda more than 500,000 women were raped during the genocide that ravaged that country. In Sierra Leon 64,000 women were raped as part of an attempt to impregnate women in order to shift the racial makeup of that war torn nation. 40,000 military rapes were reported in Bosnia Herzegovina. In the first six months of this year 4500 rapes were documented in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The UN estimates that every day 100 women are raped in Darfor. This past summer the government of South Africa released statistics that reported that 28% of South African men polled admitted to having committed rape in the past year, many of these men admitted to having raped more than one woman.

I need not tell you that the fate of women who are raped is one of shame and isolation, more often than not disease. Indeed in some places in Africa rape ends in death. The children of rape are stigmatized, abandoned and in some cases left to die. The world remains a cruel place for the mamzerim.

The church has told the story of Mary in it’s own particular way for centuries, holding up the image of unattainable femininity to women and men; an image that offers as an example of the perfect woman as both virgin and mother. That image may have suited the purposes of an institution that had a vested interest in having women behave in a certain way, but the time has come to tell Mary’s story differently. For in a world were over half the population is oppressed by attitudes that kill, maim, terrorize, oppress and enslave in poverty, isn’t it time we heard the story of a God who can do great things against all the odds. Isn’t it time to hear the story of God told in ways that liberate, empower those who have been most afflicted. Isn’t it time to hear Mary’s story told in ways that proclaim God’s plan for justice in a world obsessed with violence?

We can re-inscribe the image of Mary as the passive handmaiden of the Lord or we can tell the story of Mary a victim of abuse who with steely grit, courage and support struggles to raise her son not as a mamzer but as a child of God. The choice of how we read and tell Mary’s story will affect how we read the whole Christian story, and how we understand sin, sex, holiness, and redemption. The Mighty One has done great things for us.

Now, we like Mary, are part of God’s plan to scatter the proud and bring down the powerful from their thrones, to lift up the lowly. To help fill the hungry with good things, and to send the rich away empty. We like Mary, are part of God’s plan. Part of the promise God made to our ancestors, to Abraham and Sarah and to their descendants forever.

The truth is: Mary had the courage to say yes, to trust God. Mary had the courage to let something grow inside her. She had the courage to harbour a Child of God in her body. Do we have the courage to harbour Christ in our bodies? When the power of the Most High overshadows you will you have the courage to trust God? Will you have the courage to be a bearer of God to the world?

That’s the terrifying challenge that this story offers. This story challenges us to be at God’s disposal, to become filled with God’s life–for the sake of the world. But be warned, God-bearing is more than a little inconvenient: it can be heart breaking and even lethal. Bearing God to the world means letting some of God’s passion for the world become flesh and that can be costly.

When God sends a messenger to you, will you have the courage to say “Here am I, the servant of God; let it be with me according to your word. Will you have the courage to join the legions of Mary in bearing God to the world? Let it be, oh God. Let it be, according to your word….

May El Shaddai, the Breasted One,

who is God our Mother,

hold you in the love of Christ the Sophia of God,

so that the Holy Spirit can empower you

to follow in the footsteps of Mary

and bring God to birth in the world.

In the name of She who is was

and ever more shall be,

Mother, Christ and Spirit One. Amen.

When I was just a teenager, I was introduced to the writings of Dietrich Bonhoeffer by a wise Lutheran Pastor. I remember devouring Bonhoeffer’s “Life Together” and “Letters and Papers from Prison”. To this day, I credit Bonhoeffer for making me a Lutheran. While a great deal of water has flowed under a good many bridges since I was first enamoured of Lutheran theology, to this day I am grateful to that wise old Lutheran pastor who gave me my first taste of Bonhoeffer. Of late, there has been much ado about a little phrase that has been extracted from Bonhoeffer’s work: “religionless Christianity”.

When I was just a teenager, I was introduced to the writings of Dietrich Bonhoeffer by a wise Lutheran Pastor. I remember devouring Bonhoeffer’s “Life Together” and “Letters and Papers from Prison”. To this day, I credit Bonhoeffer for making me a Lutheran. While a great deal of water has flowed under a good many bridges since I was first enamoured of Lutheran theology, to this day I am grateful to that wise old Lutheran pastor who gave me my first taste of Bonhoeffer. Of late, there has been much ado about a little phrase that has been extracted from Bonhoeffer’s work: “religionless Christianity”.

(click here for full quotations from Letter and Papers from Prison)

“It is not for us to prophecy the day when men will once more ask God that the world be changed and renewed. But when that day arrives there will be a new language, perhaps quite non-religious. But liberating and redeeming as was Jesus language. It’ll shock people. It’ll shock them by its power. It’ll be the language of a new truth proclaiming God’s peace with men.” Bonhoeffer: Agent of Grace

Tragically, Bonhoeffer was executed before he had the opportunity to expand on his idea of Christianity beyond religion. The phrase “religionless Christianity” has intrigued agnostics, atheists, humanists, liberal christians and progressive christians. Eric Metaxas, author of “Bonhoeffer” dismisses the idea that Bonhoeffer was anything but a serious, orthodox Lutheran pastor right up to the end.

Despite the historical evidence of Bonhoeffer’s religious orthodoxy, the notion of religionless Christianity will not die. Bishop John Shelby Spong is among those who have tried to build on Bonhoeffer’s phrase and his book “Jesus for the Non Religious” has certainly moved the conversation along among progressive christians.

The dream of religionless christianity has moved well beyond Bonhoeffer as twenty-first century christians wrestle with archaic images of God and move beyond the religious trappings of traditional christianity. The notion of moving beyond religion has always intrigued me. Years ago, while studying Hinduism my professor offered a definition of God from one of the Vedas: “God is beyond the beyond, and beyond that also”. As I continue to explore the life and teachings of the man none as Jesus of Nazareth it becomes more and more evident that such a definition is compatible with his portrait of God. Jesus of Nazareth attempted to move his co-religionists beyond their religious images of God. What might our images of God become if we move beyond the idols offered to us by the religion of Christianity? Might we move toward images of God that more closely resemble the teachings of Jesus by moving toward a religionless christianity?

Sometimes we can better reflect upon our own tradition from the perspective of another tradition. In the video below, twentieth century philosopher and theologian Alan Watts explores the concept of the Religion of No Religion.

“Beyond the Beyond and Beyond that also.” Letting go of our images is the gift of faith that moves us beyond religion. I can hear Jesus call us to let go!

Jack Spong has been a great friend to Holy Cross Lutheran Church in Newmarket and over the years he has graced us with his presence three times. You can read what he has to say about Holy Cross here and here. Below you will find video recordings of Jack’s lectures at the Chautauqua Institute this past June. As always Jack is in great form and each lecture is well worth watching. If you are short on time, watch the last in the series and it will leave you wanting more.

Jack Spong has been a great friend to Holy Cross Lutheran Church in Newmarket and over the years he has graced us with his presence three times. You can read what he has to say about Holy Cross here and here. Below you will find video recordings of Jack’s lectures at the Chautauqua Institute this past June. As always Jack is in great form and each lecture is well worth watching. If you are short on time, watch the last in the series and it will leave you wanting more.

The Judeo-Christian Faith Story: How Much is History